It is said that a backup system is only as good as the trust you put in it. On the surface, your backup system is good – meaning, the trust level is high as your business success relies on it, right? But would you stake your job on the ability to restore your control room human-machine interface (HMI) within an hour of a major equipment failure or worse, a ransomware attack?

A traditional approach to backing up an automation system is to copy the current configuration, tag names and graphic files to a safe network location. Vendor tools may even automatically handle this task. But what of the underlying computer operating system? The application itself? Does your backup procedure include these programs too?

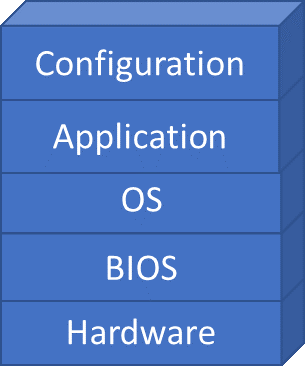

All computer systems rely on multiple software programs to create a functional system. Just above the computer hardware is the basic input/output system or BIOS. This creates the interface of various hardware components so they can be accessed in a standardized way by the next software level, the operating system (OS). For most recent HMI systems, this software is a version of the Microsoft® OS, although there are others such as Lynx and Apple iOS. Many legacy distributed control systems (DCSs) run on their own proprietary OS. Next is the vendor’s HMI application. These are the tag databases and graphics display engines that the operator uses. Last are the site-specific tag names and graphic configuration files. The vendor-supported backup configuration (tag names and graphic files) are just the top of the stack of software required for a functional HMI.

A complete installation includes the vendor application and the operating system. It should be immediately clear that the vendor’s backup will not, in most cases, be solely enough to permit a full system recovery. Note this is not necessarily the case for all vendor backups. Many legacy DCSs do back up the entire stack even if they don’t use a Windows OS, but the time to find that out is now –not after a catastrophic event.

How often does a computer failure only affect the automation system configuration files? The honest answer is that the entire stack is usually affected.

Real Life: Restoring an HMI

Let’s review a real-world situation. A severe weather event or a ransomware attack occurs at your facility. The lightning strike, flood, or ransomware attack takes down both your primary and redundant secondary server. You are not worried, because you have a solid backup of the HMI files. You call your IT staff, and fortunately, they have a replacement server in stock. Let the recovery begin.

First, you make sure the hard drive is formatted correctly. In this case, you are in luck as the partition is pre-configured, so you can skip formatting the hard drive. Now let’s get to it and get that operating system (OS) loaded.

Depending on the media used, it can take between 30 minutes and 5 hours to load Windows onto a clean computer. Did anyone back up the Windows configuration file? No? Now the entire Windows server setup must be performed. “Hey, do you have the manufacturer’s manual for the automation system? I remember that there is a specific configuration required prior to loading the vendor software.”

Finally, the OS is loaded. Now you can get the HMI software going. The disks are in the file cabinet next to the new server, but the server doesn’t have a DVD drive. Can you download the software from the vendor’s website? Three hours later the software is downloaded and installed.

Next, you go grab that backup from a USB stored in a cabinet in the data center. You begin the application installation, but after 30 minutes, you get an error. A check of the vendor’s website indicates a software patch is required for one of the features you use on your HMI. You download and install the feature patch and begin the application installation again. Forty-five minutes later, the application is fully installed.

You use the application tool to restore the configuration, tag names and graphic files. It restores without error. You refresh the control room workstations screens with fingers crossed. No new data? What is wrong? You forgot to configure the network interface cards (NIC) on the server. You find the correct IP addresses on labels on the old servers, refresh the workstations and new data populates.

Success!

In the end the operation was successful, but it was a frustrating endeavor with a lot of time, money and resources wasted on something that is easily remedied. By acknowledging that a good backup and recovery plan includes more than just the application configuration files, recovery will be quicker and more certain.

Backup Options

Now that we understand the complexity of restoring a complete HMI in a real-world situation, what are the appropriate solutions? One solution is clearly redundant servers and RAID (redundant array of independent disks). Most systems use redundant servers to ensure seamless operations and anticipate basic equipment failure. Unfortunately, this approach only handles the instance where we have an individual server hardware failure. It does not handle the ransomware infection or lightning strike with the same effectiveness.

The only method to back up the entire stack at once is to image the server hard drives. A disk image is a single compressed file, an exact copy of the computer’s hard drive, which holds all data including operating system installation, boot information, applications and individual files. When an image is restored on a reformatted, repaired or new computer, the system will be in the exact operational state as when the image was taken.

Since an HMI is dynamic, once it is restored the new field data will update the system to its current state. In some cases, operators must re-enter the constant values for setpoint and/or recipes, so hard copies of these values should always be part of a recovery plan. Despite these issues using a disk image backup clearly saves recovery time. It is the most effective way to alleviate the pain from catastrophic events, mass equipment failures and virus or ransomware events.

Image creation has some caveats, however. First and foremost, it is important to test to see that the created image itself does not disrupt the server function. Will the control room operator station function properly as an image is created? Second, how often should an image be created? Most operational systems are quite static in their configuration, but it is appropriate to make a new image every time the system is changed or modified, which would be at the same time most technicians save application configuration changes.

It is tempting to use set-and-forget disk image software. This software automatically updates a disk image incrementally in real time. This process seems ideal since no one needs to remember to make the image, but it suffers from two flaws: First, the software needs to be monitored to ensure it is working properly and updating the disk images. During a catastrophic event is not the time to find out the imaging software was turned off when the server was patched. Second, the disk image may prove to be unusable. Slowly propagated ransomware and other cyber-attacks can be captured automatically by set-and-forget disk image software, causing reinfection when the system is restored with the image. While tempting, it is better to create a disk image deliberately on a scheduled basis instead of solely relying on an automated solution.

A recovery procedure is just a plan, unless it is tested. It is imperative that the disk image is periodically restored onto a computer to see if it will function as predicted. This procedure will ensure that the image is current, valid and works on replacement hardware. Testing the recovery procedure also ensures there are no missing steps, such as not having a required cable or boot disk.

This last point is far more than academic. Changes in computer hardware are rapid, with complete architectural shifts every five years. Operating systems evolve to adapt to these changes, yet it is not uncommon for an HMI system to be in place for ten years or more. This misalignment can cause issues after catastrophic failure. Despite appearing the same, replacement hardware may have an entirely different underlying architecture, making the backup disk image incompatible with the new hardware.

Speak with a third-party automation solutions provider or systems integrator. It is helpful to have an external partner to review and look at your backup and recovery plan and procedures. Integrators deal with many systems and can apply best practices to your process. In fact, it may prove easier to outsource the backup and recovery testing. Your staff is busy, and this essential step doesn’t always rate as high in necessity as it should. Having an integrator that focuses on this specific task could be money well spent.

In most cases, it is not a matter of if but when a system will need to be fully recovered. Just remember, a good backup and recovery plan includes more than just backing up the HMI configuration files, and you should always test your backup systems. Knowing the issues ahead of time and planning and testing for the recovery will create a backup that you CAN bet your job on.

Making cybersecurity a priority and understanding the Darknet’s role in allowing others to access your control system will help keep your facility up and running without intruders running it for you. You may be wondering, Can the Darknet Harm My Process Operation?